McLaren

J. & H. McLaren

| Type: | Traction Engine Builder |

|---|---|

| Formed: | 1876 |

| Closed: | 1952 |

| Factory: | Midland Engine Works, Jack Lane, Leeds, Yorkshire, United Kingdom |

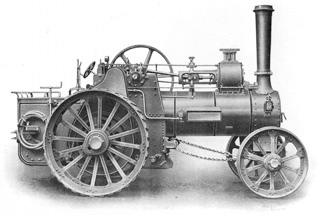

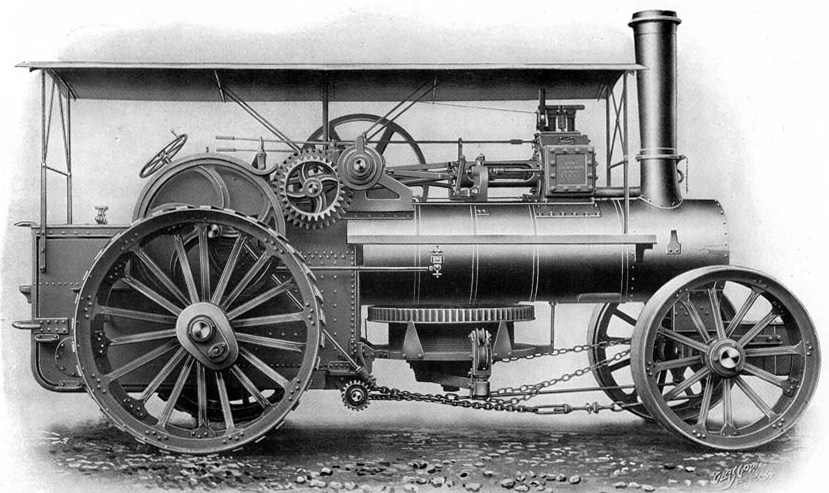

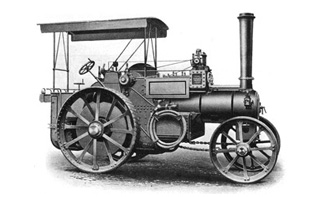

J. & H McLaren of the Midland Engine Works Leeds were formed in 1876 by the McLaren brothers, John and Henry. The company was set up within an engineering hotbed in the Hunslet part of Leeds, West Yorkshire, with several competitor companies situated alongside them. They entered the market late, most other traction engine builders were established long before them, however they developed a reputation for strong, reliable engines and the company became highly regarded by owners and operators.

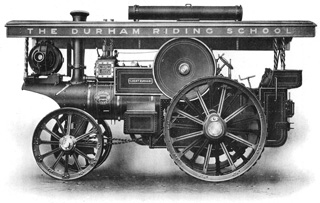

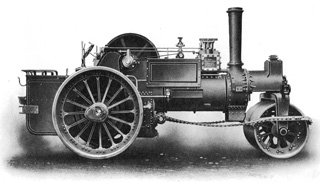

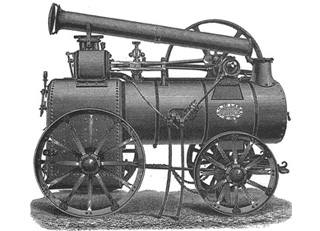

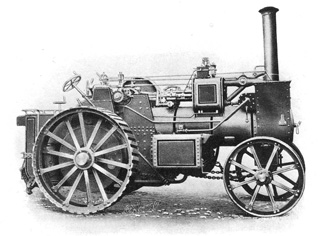

McLaren were know for their simple, effective general purpose engines, numerous and powerful Road Engines (many produced for the military) and steady output of large cable ploughing engines. They also produced in smaller numbers; steam tractors, direct ploughing engines, steam rollers and portable engines.

They had a large overseas market with sales representatives across the globe. Well over half of the steam traction engines built at the Midland Engineering Works were sold to oversea's buyers. The company was know for taking time to understand the overseas markets that they were trying to sell to. The company founders regularly visited overseas clients. A third McLaren brother, William, was employed as a sales agent in Christchurch, New Zealand and established the company in this country. There are now more preserved McLaren engine in New Zealand than the UK.

The company recognised their future was not with steam relatively early, when compare with contemporary steam engine manufacturers, and made the move into the production of internal combustion engines. Ultimately becoming the first volume builder of diesel engines in the UK, and as a result surviving as a business right up until the 1960's.

Today McLaren engines are highly regarded by enthusiasts with around 100 surviving across the globe. Numerous preserved McLaren produced engines survive in the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand. A sizeable number of engines have been return to the UK from countries such as Argentina and Patagonia.

In 2010 a large gathering of McLaren steam engines and associated equipment took place at the Great Dorset Steam Fair in Dorset, England. This was the largest collection of products from the Midland Engineering works since the factory was in operation.

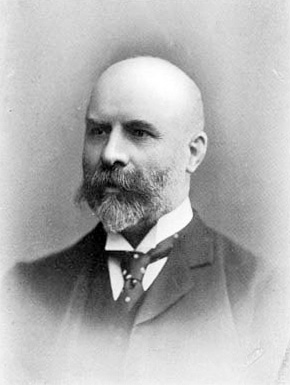

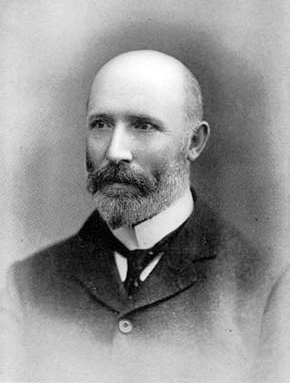

McLaren Family

The Brothers McLaren, John and Henry, were born at Hylton Castle near Sunderland in 1850 and 1854 respectively. Their parents were tennent farmers at the Hylton estate which was leased from Anthony Etterick. Originally the McLaren family had Scottish origins, coming from Overardock in Perthshire moving to Hylton 6 years prior to John's birth.

Both brothers served their apprenticeships at Black, Hawthorn & Co who were builders of various types of railway, stationary and marine steam engines. The family moved in 1863 to a farm at Offerton Hall on the banks of the River Wear and in 1869 their father Henry McLaren senior purchased a set of ploughing tackle from the Fisken brothers of Hunslet in Leeds who were early pioneers in the production of steam ploughing tackle.

Some time after this transaction Fiskin's found themselves in financial difficulty and they merged with the Ranvesthorpe Engineering Company of Mirfield in Yorkshire who subsequently made and sold the products designed by the Fisken Brothers. Owing to their associations with the McLaren family in 1871 the company interviewed John McLaren for a position within Ravensthorpe Engineering, initially on a 6 month contract. So impressed were they with his work that later he became an equal partner within Ravensthorpe business alongside Thomas Fisken and John Dixon who had provided the initial capital to expand the business. In 1871 a trial of steam tackle was held on the McLaren's land at Offerton Hall by Fisken's using a Clayton and Shuttleworth 12 NHP engine and a Fowler plough. In the following few years internal wrangling within Ravensthorpe engineering saw Fisken's leave by 1874 and the business was sold by owner John Dixon in January 1876 allowing John McLaren to leave and form his own business with his brother later that year.

During this time Henry McLaren worked for W & J Cardwell of Dewsbury although there is little written evidence to prove this. Cardwell built amongst other things sewerage pumping steam engines and there are a number of documented transactions between Cardwell and Ravensthorpe during the time Henry worked there.

John McLaren married Jane McCraken in 1881 and in the following year Henry McLaren married Jane McCraken's sister, Grace. The McCraken family were a Scottish family originally from Aryshire but had moved their farming concern to Northumberland and introduce Blackface sheep to the area. John had 4 children, Agnes, Henry (know as Harry), Helena Jane and Constance. Henry had 3 children, Henry junior who was known as Jimmy or Hamish, Grace and Jane. Harry McLaren joined the company in 1919 and was Managing Director until his death in 1943. Henry McLaren Jnr also joined the company and was know as Jimmy around the works.

Establishment

The firm of J & H McLaren was established in Leeds in 1876

Midland Engine Works

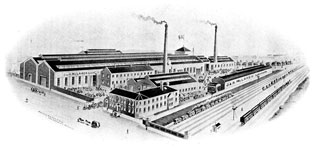

The Midland Engine Works was built by a local building contractor Hiram Broomhead during 1876 on Jack Lane in the Hunslet part of Leeds and opened for business in October of that year. Hiram Broomhead also providing a mortgage for the building and initial purchase of the land. The works was named the Midland Engine works because of it's close proximity to the Midland XXXX railway line with sidings running alongside. The area in which the companies were located were surrounded by similar engineering concerns including 2 direct competitors Kitson who had been early pioneers in steam ploughing engine production and the large and well established John Fowler and Co which would have been McLaren's main competitor. With McLaren's establishing their business much later by the time their works had been built Fowler's employed over 1000 employees having commenced business at least 16 years prior to McLaren's incorporation. There was however a steady supply of experienced engineers in this part of Leeds which is why brothers decided to choose here to build their works. In 1877 it was suggested that the company employed about 20 skilled men.

A number of stylised engravings of the works are detailed in the companies catalogues, however in reality the works were initially quite small and designed on only for the creating and assembly of engines and implements, little space was provided for the other invertible functions of the business. Slowly the works grew and absorbed other nearby buildings. In 1892 the company applied for finance to extend the works which was becoming too small for the quantity of items they were producing and the methods the chose to build these engines. The finance for this extension was not finally paid off until 1919 over 25 years later.

Many of the materials and parts used to build the engines were sourced from third party companies, generally from companies local to Leeds and the Yorkshire area. Parts to be sub-contracted out included a wide variety of important components including gears and cranks plus smaller parts such as iron and brass fittings. This outsourcina allowed McLaren to remain relatively small whilst still producing relatively high numbers of engines. It also drove costs down as parts could be bought in bulk and saved up to be fitted to engines as they moved through the factory.

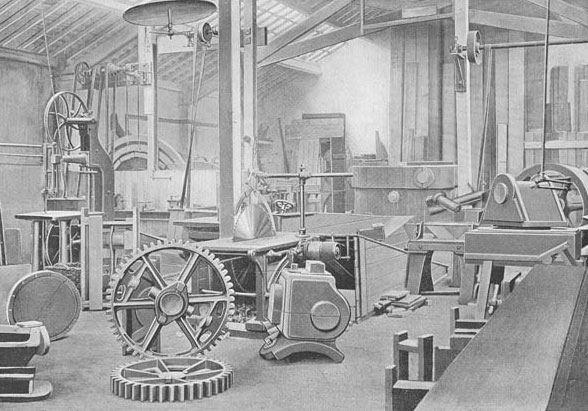

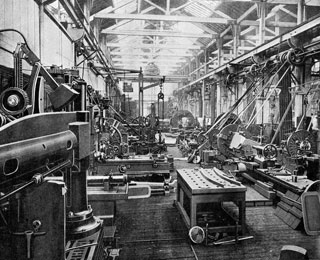

Interior Pictures

Contemporary Mclaren catalogues of the day featured stylised engravings of various parts of the factory, these would have been originally made up from photographs with variations added to suit:

Engineering Processes

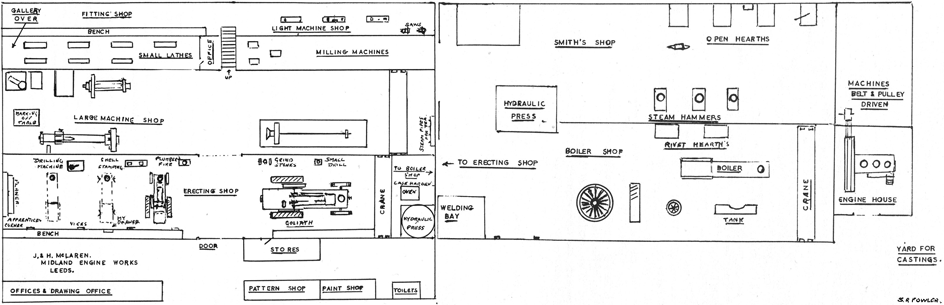

Plan of the Works

The following plan was drawn by Stewart Fowler who worked as an apprentice for McLaren's between the years of 1916 and 1920. It shows a number of areas of the factory which are not featured in the above illustrations. He wrote also wrote a very interesting book about his experiences working at the company.

The Works Today

Nothing of the McLaren factor exists today, the buildings have been pulled down to provide space for light industrial premesis.

Geographic Location of the Midland Engine Works.

Types of Engine Built by McLaren

The following list exhibits the types of engine produced by J. & H McLaren:

General Purpose Engines |

Road Locomotives |

Ploughing Engines |

Tractors |

Showmans Road Locomotives |

Colonial Engines |

Road Rollers |

Portable Engines |

Company Reputation and Innovation

Sliding Cylinder Engines

The earliest McLaren engines had an innovative feature, a sliding cylinder which fitted to a dovetailed groove machined into a mounting plate on top of the boiler. The cylinder and XXXX was then screwed to plates bolted either side of the hornplates

This system had a number of advantages, most importantly it stopped issues with expansion of the boiler when it was at operation temperature and ensured valve settings remained constant with no

also with this system less holes needed to be drilled directly into the boiler so the strength of the boiler was higher and there was less issue with steam leakage from bolt holes which need to be caulked etc.

An example of a sliding cylinder engine survives in New Zealand all be it in a incomplete and slightly modified condition. This engine is thought to be McLaren Number 2 which originally worked in the UK but was exported to New Zealand. The engine briefly returned to the UK for the McLaren Great Dorset Steam Fair event in 2010.

McLaren used this system on all of their early engines, both single and double cylinder however by XXXX they had reverted to mounting cylinders directly onto the boiler barrel as was the method other manufacturers used and remained the practice until the demise of steam in the 1930's.

Boulton Wheels

Superheating

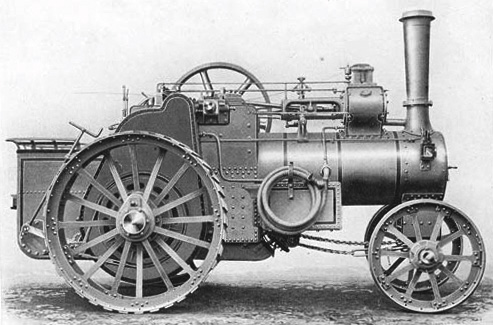

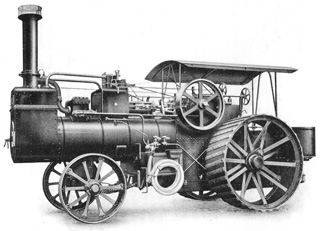

McLaren were not the only company to experiment with the fitting of superheaters to their engines - amongst others Fowler built superheated ploughing engines and to a lesser extent superheated road engines, and Garrett also fitted superheaters to some of their engines. However, McLaren were one of the leading proponents of superheated steam, a practice that was always more popular on the railways.

Superheating has the theoretical benefit that water is heated beyond boiling point and heat generated is utilised in heating the steam twice, once in the boiler and again in the smokebox before entering the cylinders at a much higher temperature than traditional 'saturated' steam engines. Superheated steam is referred to as 'dry' because of the lesser proportion of water contained within it.

Superheaters could be added to an engine in a number of ways but McLaren favoured fitting them within the smokebox, this resulted in a larger square smokebox beneath the chimney and a maze of pipe work leading from the top of the smokebox to the cylinder. McLaren's superheater was a reasonably simple affair, steam was fed into two pipes then feed through two coils, into a second set of coils before being combined together and piped into the cylinder. In 1910 they submitted a patent for their Superheater arrangement, specification 27260.

Conversional wisdom is that the benefits of superheating are seldom required on a traction engine because it is rarely working at full power for long periods. McLaren claimed however that their superheated engines reduced coal consumption by 12% or more.

McLaren engines were also fitted with a feed-water heater which heated the water entering the boiler to near boiling point, thus increasing efficiency further.

Along with the increased costs associated with building a superheated engine, they were more difficult maintain and the superheating elements within the smokebox required careful cleaning to remain efficient there was also the requirement to use none standard lubricating oils because of the dry nature of superheated steam which were an additional cost to bear for the operator and sometimes difficult to get hold of. Superheated engines represented only a smaller percentage of McLaren's total output and they did not experiment with build superheated ploughing engines as Fowler's did. A number of superheated engines which were shipped abroad have returned to the UK however no steamable examples are in existence at present.

Legal Action by Aveling & Porter

Overseas Markets

From the very beginning the company looked to develop it's overseas markets, and one of the first engines they produced was sliding cylinder engine number 38 which was supplied to the Sultan of Zanzibar in 1879, a couple of years after they built their first engine for the home market. Both John and Henry McLaren travelled extensively throughout their careers with the company to view their engines in action overseas and access potential markets, they were firm believers that if their engines were to be successful they need knowledge of the working conditions they would be subjected to.

Part of this interest in overseas markets was through necessity, owing to their late entry into the engine building business much of the UK market had been sown up by competitor companies, not least their close neighbours Fowlers. The overseas markets such as Australia, New Zealand and South America remained relatively untapped in the late 1800's however.

Following a visit to Australia and New Zealand by Henry McLaren in 1887 a branch of the company was opened in Christchurch, New Zealand under the name of W.A. McLaren Ltd, the operation being ran by a third McLaren brother, William. This business dealt with many different area's associated with the parent company including, selling of new engines and implements, repairs to engines, goods haulage and contracted threshing. In 1898 the New Zealand business was sold to a Henry Holland who had been born in Yorkshire but emigrated during his childhood. Traction engines, road rollers and portable engines were all supplied to the New Zealand market, a number of which survive to this day.

McLaren used a couple of Australia companies to sell their engines; Gibson, Battle & Co Ltd who were based in Sydney and Gibbs, Bright & Co in Melbourne - this company was operated in conduction with Peter McLaren, another brother of John and Henry. Over 200 McLaren steam engines went to Australia including large traction engines, cable ploughings engines, stump pulling engines and even two semi-portable engines for use in pumping stations.

South American operations were covered by a company called Scavill, Rosario, Argentina which later became Topping, Scavill & McLaren, the McLaren being another brother of John and Henry, Robert McLaren. This company was setup in the early 1900's and supplied their first engine 840, a 10NHP straw burning example in 1906. They subsequently supplied around 100 repeat orders, almost all being similar 10NHP engines which burnt straw. A number of these engines survive today and have been re-imported back to the UK.

Other agencies who supplied McLaren products included Caccia Lonza & Brungini in Italy, Dalrymple in Johannesburg in South Africa and Friedrich Dehne in Germany.

Engines produced for overseas markets differed to those produced for the UK. As mentioned the South American engines were large straw burning engines, simple in build as spare parts and those with the skills to repair any breakages would have been in extremely short supply in this part of the world. Road engines with and without superheaters were also produced for the South American market. Engines built for sale in New Zealand and Australia where generally larger than engines for the home market, generally comparable in size to a Road Locomotive produced for the UK. These engines had to endure tough conditions hauling heavy loads across unmade roads and sometimes over open fords which required the fire to be dropped. McLaren made extensive reference to these tough conditions in their marketing literature, proudly proclaiming that despite this abuse engines ran for over 2700 miles with 20 ton loads without any form of breakage.

Finish Applied to Engines

McLaren usually painted their engines black. They were lined with a mid-brown, then red, followed by yellow line. This was very similar to the finish applied to the majority of the engines produced by their near neighbours, John Fowler & Co. Unlike Fowler's wheels were painted red or orange with simple single lining in yellow.

Right can be seen an example of original paintwork as applied by McLaren in 1917 to engine 1434 - this engine was recently returned from XXXX in an unrestored state; a rare example of the original finish still on a McLaren engine.

McLaren also fitted very little decorative brass work to engines, some had hardly any. Makers name and number were generally cast into the cylinder rather than inscribed on a brass plate as was popular with most other engine builder, chimney tops were cast rather than brass or copper, cylinder covers were cast and not fitted with brass covers and smokebox rings etc were either not fitted or cast in gun metal rather than more expensive to product non-ferrous metals.

This lack of embellishment was sometimes due to necessity, McLaren supplied a sizeable number of engines to the war department who would have not been willing to pay for these additional brass items.

The company did produce a number of showman's engines, famed for their brasswork and decorative finish, but they did not pursue this market for long and the only the only surviving McLaren showmans engines we have today were not originally built for showland customers and converted at a later date.

Associated Equipment

Ploughs

Cultivators

Traction Wagons

Sleeping Vans

McLaren's Improved Sleeping Van as the company described them was built for the lodging of men engaged in threshing, rolling or ploughing contracts.

The vans were very similar in appearance and size to their close competitors Fowler's who built considerably more. Only one McLaren sleeping van survived into preservation.

Wash-out Pumps

Demise of Steam

McLaren produced their last engine in 1938, XXXX a crane engine which went to South Africa and survives at the XXXX museum in Johannesburg. However, steam production had started to wain more than 20 years before this when McLaren became involved with the production of industrial internal combustion engines and in 1926 they signed an agreement with the German company Benz to build diesel engines for road, rail and agricultural purposes thus becoming the first volume producer of diesel engines in the UK. It was because of this switch that the company managed to survive far longer than most other former steam engine producers.

Ploughing Engine Diesel Conversions

The company also found a niche converting several sets of ploughing engines to from steam to diesel power

In 1945 the company took of the remains of their Leeds neighbour Kitson and Co and

McLaren Engines in Preservation

Around 100 McLaren steam engines survive across the globe, the majority in New Zealand. XX engines survive in the UK and Ireland, these numbers have been swelled considerably by the reimporting of engines from countries such as Argentina, Patagonia and Australia.

| Type | Surviving UK Examples |

|---|---|

| General Purpose Engines | 50 |

| Road Locomotives | 50 |

| Ploughing Engines | 50 |

| Tractors | 50 |

| Showmans Road Locomotives | 50 |

| Colonial Engines | 50 |

| Road Rollers | 50 |

| Complete list of Surviving UK Engines | |

Great Dorset Steam Fair 2010

The 2010 Great Dorset Steam Fair saw a special gathering of McLaren engines organised by McLaren 1534 owner John Wakeham.

Publications

- The Iron Men of the Road - Tam McTaggart. A Publishing Company, 1989. ISBN: 9780907526414.